This interview was conducted by Jonathan Homrighausen.

© Pictures provided by Galia Goodman

Jonathan Homrighausen is a calligrapher and a doctoral student in Hebrew Bible/Old Testament at Duke University. He is author of Illuminating Justice: The Ethical Imagination of The Saint John’s Bible (Liturgical Press, 2018), and his own work may be seen at jdhomiecalligraphy.com.

Over warm cider one Friday afternoon, I sat down with Judaic artist Galia Goodman to chat about her latest project, The Promise of the Land: A Passover Haggadah(Behrman House). This ecological haggadah was written by Rabbi Ellen Bernstein, and Galia contributed the dozens of artworks beautifying the seder. Galia lives and works in Durham, North Carolina.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your background.

I have been doing Judaic art for 36 years—starting with extremely simple papercuts and continuing into far more complicated designs. In 1986-87, I attended Ulpan Etzion in Jerusalem and studied Hebrew calligraphy with Izzy Pludwinsky.

I found myself inspired by all of the artifacts in the Jewish Museum: the architecture, mosaics, and archaeology from that land. You can’t go to Israel without being bombarded by the sights and smells, the cultural milieu, the incredibly broad collision of cultures in that area. For an artist, the country is a rich trove of material, not least of which is the land itself.

What inspires you about the land?

Having grown up in Colorado, I came to Israel with a background and appreciation for natural beauty. People tend to imbue Israel with some kind of special status because it is the land that God gave to the Jews.

Without denying that, I feel that when you say the land, you really ought to be saying the earth. It’s the gift that all human beings have in common and that most of us don’t appreciate as much as we should. Even before working with Rabbi Ellen, I had come to this conclusion as an environmental activist, as a long-distance hiker, as someone who walks everywhere I go when I can. Anywhere in the world, I am in touch with the land.

How did you get into this haggadah?

I have been hiking the 2,200-mile Appalachian Trail for the past several years. While I’m on the trail, I take many, many photos of textures, colors, patterns, and landscapes to paint when I get back to the studio. Ellen was looking for an artist for her haggadah, googling for ecological Jewish artists, and found some of those collage and acrylic paintings of sites from the trail. This came out of a clear blue sky.

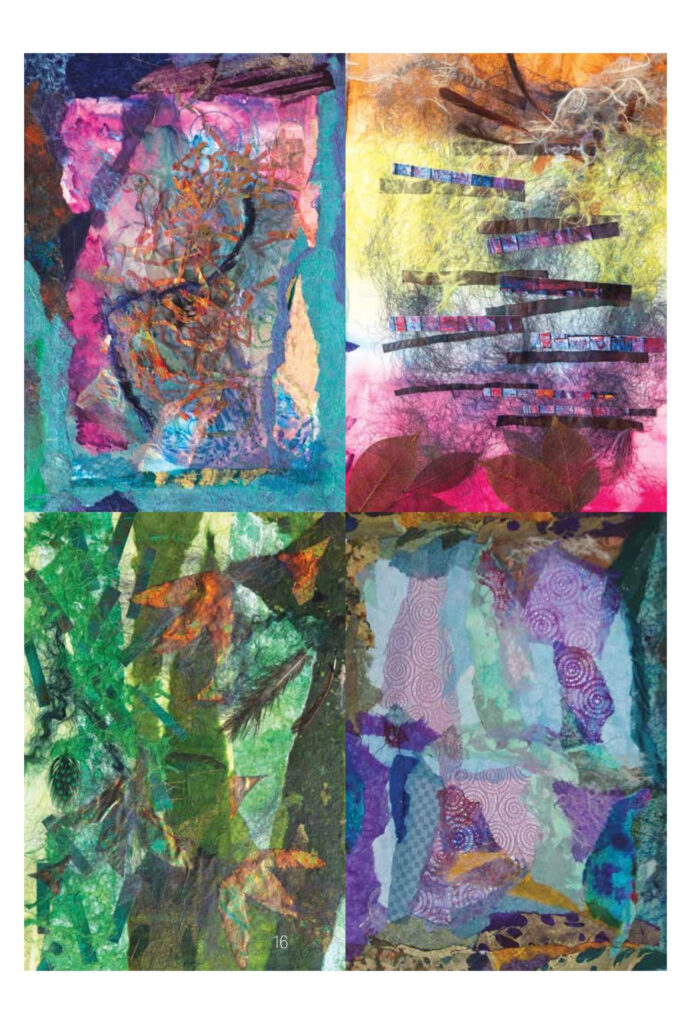

Turning to the haggadah itself, I see different styles of art. You have the usual Pesach symbolism, but before turning to that I want to ask about your abstract pieces. How do you work with abstraction? How does it relate to the text of the haggadah?

I find a lot of quotes I want to illuminate, and I often do so by pairing quotes with colors, patterns, and textures. These won’t speak the same way to everybody. If they do, it’s bland. I’m trying to spark responses based on what viewers feel, to strike a chord artistically and emotionally.

Some of the abstract patterns in the book are taken from work I did previously, work which Ellen saw on my website and picked out for the seder. So some of the abstract patterns relate to the seder texts in ways which she saw, even though I didn’t create those works for this haggadah. I welcome that kind of response!

Can you give an example?

Certainly! The page with four different abstract pieces depicting the four children: the wise, the rebellious, the simple, and the one unable to ask. The top-right image, to Ellen and me, depicts the rebellious child, the one who puts up walls and resists.

I had interpreted that one as the wise child! I thought of the rectangles as building blocks of knowledge, with which the wise child asks an insightful question.

So you see: abstraction enables multiple responses!

What about the collage? What do you like about this medium?

The collages give a three-dimensional feeling to the work. It’s different from something just painted. There are shadows from raised surfaces.

I use a lot of natural objects in collage: leaves, twigs, feathers, sand, paper scraps, cloth, plastic. I try to inculcate the idea that you can recycle just about anything and make it into art. I’m not the first to do that. I’m inspired by my friend, fellow artist Bryant Holsenbeck.

So it’s not just visual. Your work is tactile. It reminds me of the rabbinic saying that every Jew is supposed to feel as if they personally escaped Egypt. Bringing in more beauty, more senses, makes the story more vivid, more alive.

Exactly. The tactility of collage is intimate.

One thing I liked about working with Ellen was having both this openness of interpretation as well as the creating images immediately recognizable. Take the Hillel sandwich on page 51. My image of the Hillel sandwich is not neat and tidy. The sandwich itself isn’t. By this point, neither is the seder. It’s both sweet and bitter.

What was your favorite image to create?

The vineyards depicting the first fruits of the land. They were fun! The goat was cute too.

I also really enjoyed doing the seder plate. I created the plate and the food items separately, then arranged them in many different ways and sent the photos to the publisher. It was like playing with Legos: building from scratch, arranging.

Most of the big landscapes are from photos I took on the Appalachian Trail. The cover of the book is the Blue Ridge Mountains above the Shenandoah Valley.

What does the Passover story mean to you?

Two things.

First, Passover has always been a cautionary tale. It’s the story of going out from Egypt, the end of 400 years of oppression from pharaoh who did not remember the work of Joseph. Joseph, as we know, saved the Egyptians from famine. After this, the relationship between the Israelites and the powers of Egypt soured—and all of this takes place in a few verses at the start of Exodus. It was nothing but disrespect and ignorance of history that led the later pharaoh to treat Jews badly. God punished that pharaoh because he didn’t know his history.

This tells me that we need to remember history. We should acknowledge those who did good. We should be skeptical of bad reports about despised minorities, like the slander about the Jews that the Egyptians circulated.

Second, in the haggadah we are often told that God gave Israel the land. But God never gave the land, God only lets people live on the land, to take care of it as a place for all to thrive on. If you go to a land and you don’t consider those who already live there—like the Native Americans in this country—my environmentalism demands that we start looking at the land not as something to benefit one group, religion, sect, or nation, but to benefit all.

Profit should not be the main way we use the land. I want people to be responsible for the earth. You can use it, but should not abuse it. I’m all about the commons: community gardens, public parks, things that help people see that we all have a part in caring for, treasuring, nurturing the living things of the world, which are the inheritance of future generations. They belong to everybody. It would be nice to have this inheritance to pass onto future generations.

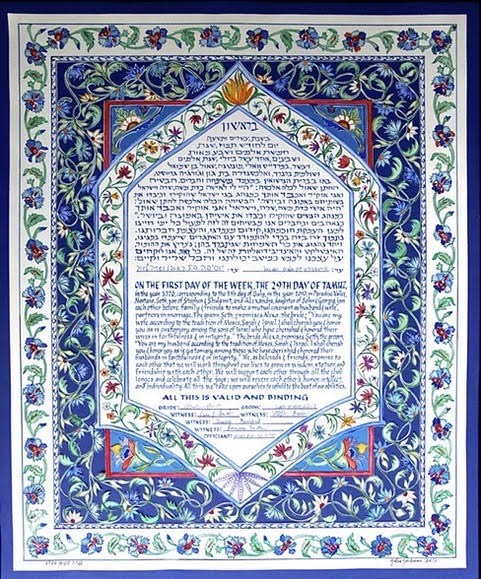

What is your next project?

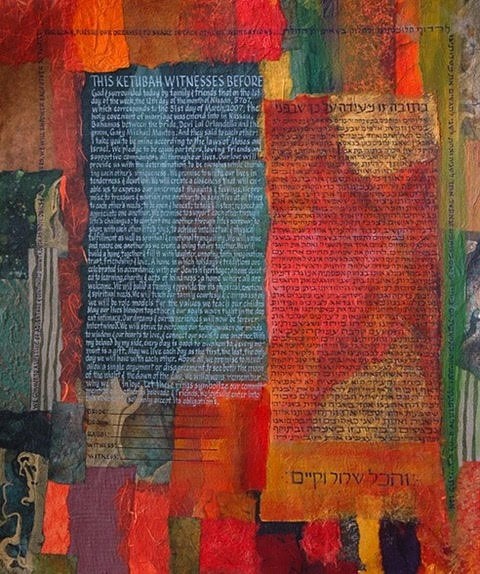

I have another group of photos from the trail for a new crop of landscapes. I am thinking of a set of smaller pieces, patterns of rocks and trees from the trail. As always, I have commissions. I do all my ketubot from scratch—no print-out patterns—and create 4–12 per year.

My ketubot alternate between traditional floral and geometric symbolism with papercuts and more abstract designs.

If I want to buy your work or commission a ketubah, where can I contact you?

Check out my website, galiagoodman.com, or email me at galiaarts (at) gmail.com.